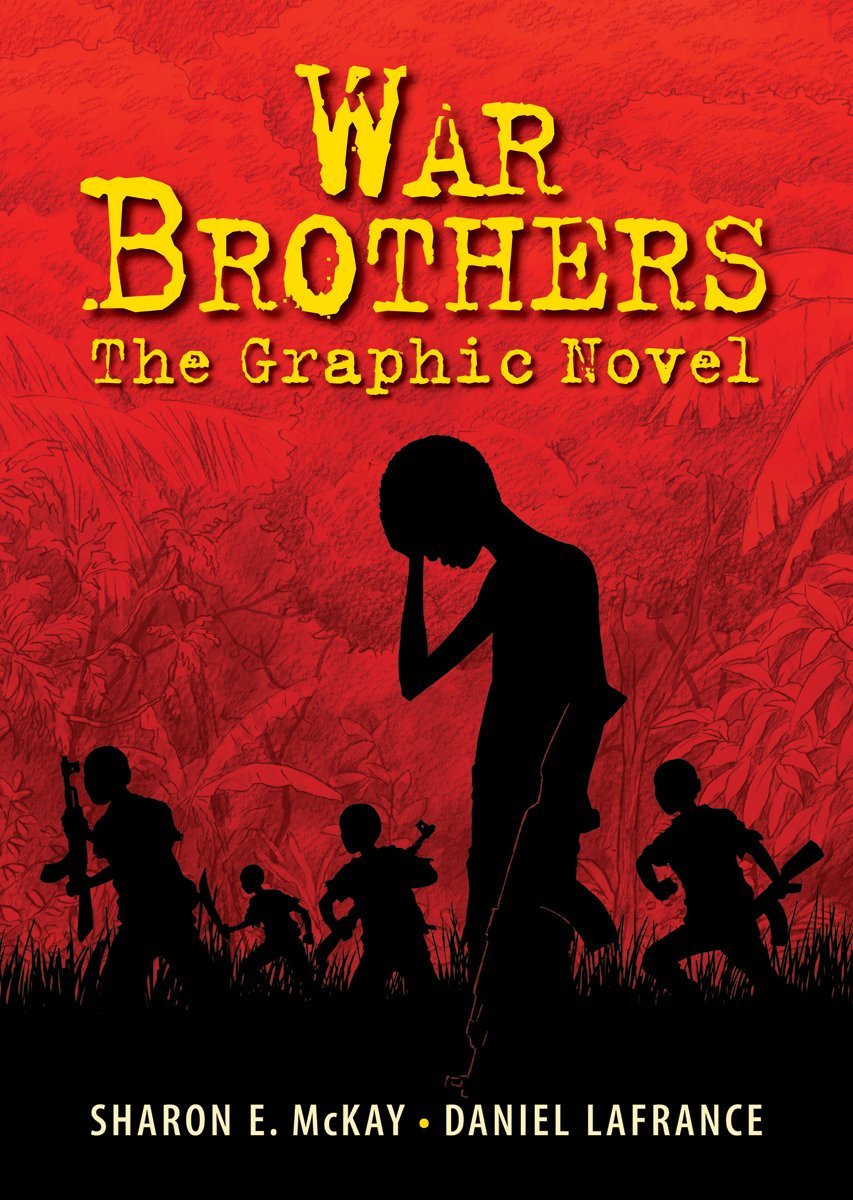

War Brothers: The Graphic Novel by Sharon E. McKay and Daniel Lafrance, illustrated by Daniel Lafrance

If you look at the bottom of this post at “Filed under,” you’ll see this title is listed as both “Fiction” and “Nonfiction.” That’s not a mistake – and the explanation is found in the book’s “Postscript”: “This is a book of fiction based on interviews in Gulu, Uganda. Everything that happened in this book has happened, and is happening still.”

If you look at the bottom of this post at “Filed under,” you’ll see this title is listed as both “Fiction” and “Nonfiction.” That’s not a mistake – and the explanation is found in the book’s “Postscript”: “This is a book of fiction based on interviews in Gulu, Uganda. Everything that happened in this book has happened, and is happening still.”

In 2002, 14-year-old Kitino Jacob begins writing his story on a lined notepad in his childish hand: “My story is not an easy one to tell, and it is not an easy one to read … There is no shame in closing this book now,” he warns. As if to underline the warning, for those who decide to continue, the panels depicting the most harrowing parts of the story are ominously edged in black.

Joseph Kony, guerilla leader of the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) – populated by stolen and brutalized children – is terrorizing then entire country of Uganda. On the eve of traveling to their school, Jacob and his friend Tony are assured of their safety: “Kony cannot get us. Do not be worried. We are safe. I heard Father talking to headmaster Haycoop about hiring extra guards to surround the school. There is no reason to fear Kony and his rebel soldiers.”

But on the first night back at George Jones Seminary for Boys, a motley gang of LRA recruits murder the adults and kidnap the students. “It’s true … they’re just kids!” Jacob immediately realizes, but these are the very ‘kids’ who force Jacob and his friends to kill or be killed. They are starved, abused, and turned into murderers. The “good boys,” he learns, “become especially mean, especially dangerous,” like Tony who once aspired to be a priest but is quickly transformed into a killing machine. Somehow, Jacob manages to hold onto his humanity, convinced that his father will save him and his friends.

Last year saw a fervor of Kony-related activity in the media: from the film, Kony 2012, which went viral, to the filmmaker’s public breakdown, to the outcry of what happened to almost $20 million in donated funds to the film’s producing company Invisible Children. “While Kony has lost much of his power, he continues to carry on his crimes across the border in the Congo and DRC,” Jacob explains in a final closing letter dated 2012 at book’s end. That Kony remains free is terrifying, but his LRA – as diminished as it is – represents only a fraction of the estimated 250,000 child soldiers in the world. What these children must endure after surviving war in order to even attempt to return to their former world will be an even greater battle.

While capturing the horrific tragedy of the life of child soldiers, co-creators Sharon E. McKay and Daniel Lafrance also manage to offer inspiration: war decimates, and yet everlasting bonds can also be forged. “[T]his is also a story of hope, courage, friendship, and family,” Jacob reminds. He echoes his friend Hannah, “… that if the world knows that child soldiers suffer unimaginable cruelty and pain, then help will come. I hope this is right.”

With testimony as formidable as War Brothers, we can’t say we didn’t know. And now that we know, we must help, offer hope, and make change. That’s a mantra for us all.

Readers: Middle Grade (with caution), Young Adult, Adult

Published: 2013

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Discussion